Aspen Art Museum

SEEING DOUBLE

Following its premiere at Tate Modern in London, and versions in Cologne and Toronto, for this iteration of the Warhol exhibition the Aspen Art Museum invited artist Monica Majoli to reconceptualize its staging, utilizing personal artefacts and archival materials alongside artworks. In conversation with Simone Krug, Majoli explains her queer affinity for archives and her aim to reveal Warhol ‘as a concept and as a person’.

The deep dialogue that some artists engage in with other artists and their work is an understudied subject, and one that is important to me. Warhol is at once familiar and mysterious, so it was key for me to invite artist Monica Majoli to think about how to look at his work and life anew: to imbue this artist we think we know so well with a different kind of life. —Nicola Lees

SIMONE KRUG

‘Andy Warhol: Lifetimes’ looks at Warhol’s life as a parallel to his work. So, I wanted to start by speaking about intimacy and the relationship that you’ve developed through the research stages of putting this exhibition together. We’ve talked about how his images are so familiar and so iconic that they’ve become distanced within a canon and yet, at the same time, Warhol is so present.

MONICA MAJOLI

I’ve always admired Warhol. I think of some of his work regularly — the early works from the 1960s, his early portraits of Jackie [Kennedy Onassis], etc. The ‘Death and Disaster’ series, which he began in 1963, was important for me because of its extremity. Also, the way it dealt with temporality and touch, and the mediated image. I discovered things about Warhol through the years, but I never did a deep dive into his life. I didn’t have preconceptions about who he was. I’d had a more abstract idea of him, through images of him, and I’ve always been much more focused on his work. I don’t recall ever having closely read his diaries before.

Emphasizing archival materials seems like a way to make his life palpable in a different way, so that it’s not all about the work that we know so well, but it’s about these materials around it that can make the work feel new again and connect to him, as an artist, but also as a person.

SK

We’ve done an immense amount of research through this process. What was surprising to you?MM

The complexity of Warhol’s personality. You wonder how he reconciled certain things like being a devout Catholic with his relationship to sex—voyeurism, his homosexuality. When I read about him, part of what was surprising to me was how vulnerable, insecure and endearing he was. There was a sweetness to him; he was a romantic.

There are interesting ways that Warhol operated and what I’m finding compelling is how that doubles back or reflects, somehow, his personality or his life story. It’s like a puzzle. There were so many different periods of his life and work and a multifaceted quality to his practice. But then there are also through-lines, and his personality is reflected in these different modes of making.

SK

To take a step backward: it’s such a curious gesture to ask an artist to reflect on Warhol — someone who changed American culture in major ways — and for them to reimagine the life and work of someone so iconic.This show comes to Aspen after a European and a Canadian run, and I wanted to know what changes or reconceptualizations felt necessary in presenting the show in the US? And what new perspectives were interesting to foreground for you as an American artist?

MM

I think there’s a general understanding or comprehension of Warhol here in America. I’m assuming a familiarity with American culture — that we have shared reference points to Warhol’s world. So, when I’m thinking about reconceptualizing, I’m doing so for an audience already knowledgeable in a particular way—even if it’s just with American culture, as a lived experience.Because of our ‘comfort level’ with Warhol and how he’s almost invisible to us, I’m interested in the things that might make him more visible and more surprising to an American viewer. I think this could be partly by looking at different periods of his work, allowing projection, and considering how it might be about common themes. For example, in the ‘queer galleries’, it was a lot of fun for me to work with that material. I was, in a way, inhabiting his position as a gay man of a certain era. Making associations freely and with pleasure — like Camouflage [1986] — I enjoyed working with that painting within a queer context. I’m not sure what that would be camouflage for; it’s certainly not going to disappear into anything. It’s so camp. But, to me, as a gay person, it also relates to the homoerotics of the hypermasculine motifs that are often circulating in the gay masculine world. And that was interesting concerning the idea of the closet. At the same time, it points to Warhol as a cipher, disappearing, as he often seemed to want to do, into a recorder or a camera.

SK

To become a machine.MM

Become invisible, blank, a screen for projection. Become a mirror, which is what, in so many ways, he was. Then there are the ‘Oxidation’ paintings [1977 –78], which suggest sexual activity in a bathhouse, a kind of orgy on the canvas — also dealing, of course, with [Jackson] Pollock and abstract expressionism. Imbuing these works with sexuality was particularly interesting to me as a queer person.SK

During the 1970s, homosexuality was considered politically charged and under threat in American society. It only became legal as late as 2003 in the US for two consenting adults of the same gender to have sex. So, Warhol was a dangerous figure because he was making and showing this explicit erotic work of men. You’re bringing a lot of sexually charged material into this show and your practice pictures queer bodies, foregrounding homosexual experience. I wanted to ask if you could talk more about your process in organizing and sifting through all of this deeply homoerotic material and how you chose to present it?MM

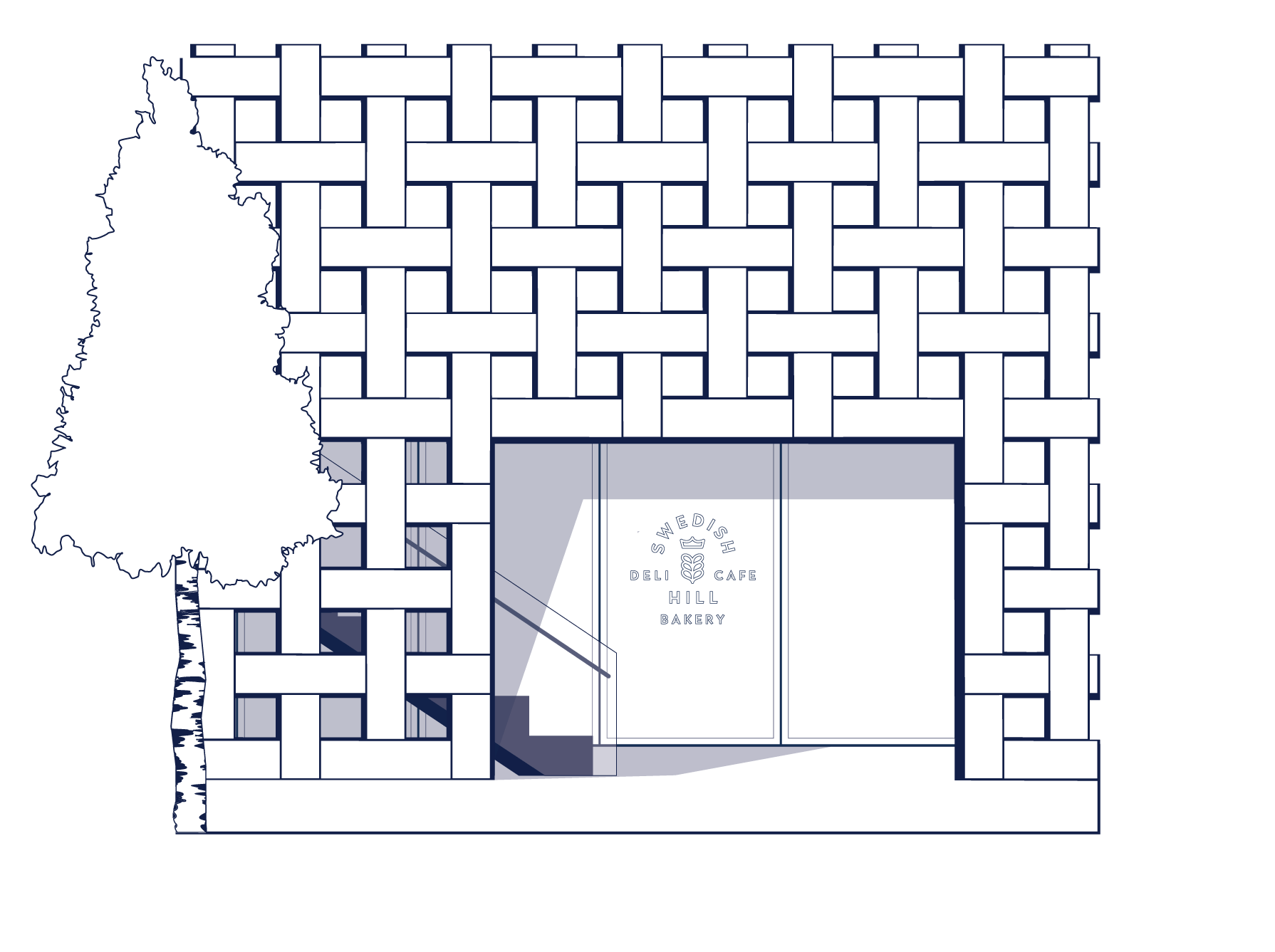

With this show, you don’t have to start at one point; you can start anywhere. In many ways, it is a collage. Part of what was interesting to me was the potential for someone to enter the ‘queer galleries’ first and have Warhol’s queerness facing the street.The gallery with the ‘Ladies and Gentlemen’ series [1975] is an immersive experience — with the spectator’s reflection in deeply saturated, mirrored plexiglass, joining with the color-infused filters that Warhol placed on his subjects, the drag queens. Also, Warhol himself in drag projected large. There’s potential for confusion within this queer, transformative context.

SK

We’ve spoken so often of Warhol’s body and his vulnerability, his desiring gaze, his awkward features that he was really embarrassed about and the scars on his torso, following the 1968 shooting by Valerie Solanas. I wanted to ask how you thought about bringing this major, life-altering event into your vision for the exhibition. And how Warhol’s life experiences and, perhaps, just his experience of being alive, unfold throughout the galleries.MM

There’s something sacrificial about the way Warhol presents himself in the photograph taken by [Richard] Avedon after he’d been shot. The pose that he struck … it’s not Saint Sebastian, exactly, but there was something very …SK

Homoerotic.MM

Homoerotic, yes. But Warhol was obsessed with beauty. And it’s so interesting that he presented his body that way such a short time after the shooting. He referred to his body as a Dior dress. It was so spliced up, so dramatically reconfigured by the shooting, and of course, by the surgery. I think that’s a fascinating aspect to Warhol, that he was both cloaked and, at the same time, so generous with his image.It was striking to see his body because he cut a pretty glamorous figure in the 1960s — a radical change from the nebbish adman he was initially. He transformed himself into this cool guy with leather jackets and dark glasses, pointy boots, striped shirts. It was a hardening in terms of his image. It brings to mind the observation by Diane Arbus, cited in an article in Art in America in 2005, about the gap between intention and effect. Not knowing whether or not he was delusional about his self-image. Warhol underwent such a physical transformation over the years. It seems like there becomes a battle for self-preservation through the image that he was creating. I think that resonates today in a way that it might not have resonated earlier; there’s such a sense of image-consciousness now, in part due to social media. But when I look at images of Warhol through the years, I see someone struggling for a sense of peace within his self-image and, potentially, a kind of dysphoria.

Coming back to your question about what was surprising — what struck me was that it took a while for the public in the US to catch on to Warhol’s greatness. It wasn’t until the show at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia that he was fully acknowledged as a phenomenon.

SK

In 1964, yes.MM

There was a resistance to Warhol. Before that, he was better received in Europe than he was here. In the later years of his life, after the shooting, he started doing a different kind of work —Interview magazine, Warhol TV — basically working with popular culture directly. Not so much a response to pop culture, but actively creating the material of popular culture of the period.The shooting resulted in a radical change. Essentially, he had a second life and that second life took place differently — it had to do with society people and their portraits, portraits of celebrities. Due to a desire for safety, his studio life changed drastically. It shifted from drug addicts, people on the fringe, anybody stopping in — somebody like Valerie Solanas — to a business model.

It became a Brooks Brothers lifestyle that allowed him a renewed sense of safety. At the same time, I think you can see a through line between his early work and his late work. And even between his commercial art and his late work, which became very commercial in so many ways. He became a product himself.

SK

He shifts from the 1960s to the 1970s; he really mirrors the way that American society and American culture change.MM

That’s true.SK

And it’s curious because 1968, 1969, those years of such dramatic global shifting — it’s this moment in history that he’s mirroring.MM

That’s so true. US Senator Robert Kennedy was killed three days after Warhol was shot. The 1960s, ’70s and ’80s were so wildly different to one another in terms of culture, and I might even say in terms of celebrity. The product endorsement — no one held a candle to Warhol regarding exploiting that opening. He became the quintessential artist in mainstream American culture. It was as if he became a network.SK

Do you think it was transgressive that he straddled so many different worlds: true mainstream pop culture, a television show like The Love Boat [1977–90], advertising?MM

I think it’s unusual for an artist to take on the kind of authority that he gave himself. That’s a radical and transgressive thing to do. To produce content for mass consumption is not usually how artists imagine their role in society; I think artists imagine themselves as critics of a larger culture.SK

Also to have no limits.MM

And have no limits, exactly. To imagine that a very idiosyncratic vision might be understood by many people or should be a part of daily popular culture. That’s a fascinating approach. When you watch Warhol TV, you see how different his version of cable television might be from the average cable show or mainstream television.SK

So many of the things Warhol did as an artist are defining features of American culture: how he saw the world, how he used pop culture as his medium. It’s impossible to decouple popular culture from Warhol’s interpretation of it. For you, is this a challenge, a curse or helpful? How did you approach this in your reconceptualization and reimagining of all of the exhibition material?MM

It is all of the above.The thing about Andy Warhol is, he’s too much to wrap your brain around. His impact has been so enormous, so dispersed. He redefined the way we see reality.How many times a day do you hear the quote about everyone being famous for 15 minutes? Even though that may be a quotation from someone else attributed to him, he decided to make it his own. An interesting thing about Warhol is how he gave himself enormous authority and, at the same time, he also wasn’t very particular about authorship.

So, when you ask if it is a curse, I would say that it’s hard to get your bearings within an exhibition of this magnitude and with an artist of this magnitude. It’s almost like his influence has sunk into the soil of our country. Things have grown out of it. He has infiltrated various ways in which we think about the country so thoroughly that it’s hard to separate out American culture from Warhol. It’s hard to separate the 1950s from Warhol and how we understood a certain kind of innocence; he made us see things critically in a way that hadn’t happened before. The way I’ve dealt with Warhol is really to think of him both as a concept and as a person and just try to move more deeply into him as an individual. He was so human.

SK

The archival dimension of the show is something that’s felt very key, especially in the idea that history is carried through the individual. The archival material and documentation creates a tangible connection to this person, and a richer understanding of the work itself. How did you get to the archive? What made that feel important? And at what point did you realize that it was going to be such an integral part of ‘Andy Warhol: Lifetimes’?MM

I felt it was something that I wasn’t familiar with seeing. The materials we received from Tate Modern felt like the beginning of something that we could explore in Aspen that maybe hadn’t been unpacked as fully.As with a lot of queer artists, I am very interested in the archival. Our history constantly feels like it’s subject to erasure. Over the centuries, queer people have read between the lines of left-over materials, which remain because so many lives have been lived in secret. So, I’m used to thinking about archival materials as a way to feel connected to my tribe.

I don’t think any artist really wants their work to be reduced to their biography. I was interested in emphasizing Warhol as a maker. I wanted the work not to feel so distant, so iconic, but rath- er that we were looking at work made by an artist at a certain point in time. In a way, I was trying to rewind the tape on the work, as much as I was rewinding the tape on his life.